Masterclass Webinar: Responsible Sourcing Considerations for the Clean Energy Transition

The global transition to clean energy is crucial for combating climate change and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. However, the production of clean energy technologies heavily depends on mineral extraction, raising concerns about responsible sourcing and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues. TDi Sustainability’s report “Material Change for Renewables” provides significant insights into responsible sourcing for the clean energy transition.

TDi recently hosted a Renewables Report Webinar, showcasing the report and highlighting key challenges in mineral supply chains for solar panels and wind turbines, while exploring effective approaches and resources for overcoming these challenges.

Presented by responsible sourcing experts from TDi and Equitable Origin:

– Assheton Stewart Carter | CEO, TDi Sustainability

– Zandi Moyo | Senior ESG Analyst, TDi Sustainability

– Jen Turner | Energy Director, Equitable Origin

– Soledad Mills | Senior Vice President, TDi Sustainability

Watch the Webinar Recording Now

Download the Report

Download the Material Change for Renewables report and contact us to discuss how TDi can support your company’s evolution to clean energy.

Download the free Material Change for Renewables report

The Material Change for Renewables report is a summary guide that looks into responsible sourcing for the clean energy transition. It is a must-read for companies and stakeholders driving the evolution of clean energy.

Download the pdf to gain crucial insights into the challenges and considerations surrounding renewable energy technologies.

Download the report

Read the webinar transcript:

Assheton Carter

Welcome, everybody. And thank you for joining us today.

I’m Assheton Stewart Carter, I’m the CEO of TDI sustainability. Looks like we have a good participation today and from the poll looks like the majority of the people from industry and interesting to see that poll response about the level of concern regarding the minerals and metals in the renewable energy supply chain, which is perfect for us because we’re here today to talk about the findings from a recent report that the TDI team published on responsible sourcing considerations in the clean energy transition, and in particular, the renewables industry, both wind and solar.

In the report, we set out to have a summary guide for producers and purchasers of clean energy and renewables and we examined some of the key challenges that lie in minerals and metals supply chain, which my colleagues will talk about a little bit later. And I’m joined by those colleagues here today, from TDI; Soledad Mills and Zandi Mayo, and together we are going to introduce a report summarising the key challenges and responses to those challenges that we’ve identified.

We then have a panel discussion, and I’m joined by two guest panelists, alongside Zandi and Sol, Jennifer Turner from Equitable Origin is the the Energy Director. EO is a standard-setting organisation amongst other things, and they have just recently published their consultation version of their Standard on wind and solar.

And then Joel Frijhoff; we are incredibly lucky to have him to come and join us for questions, who is from Orsted, the Global Energy Utility. We have also set aside time for audience questions and answers. At the end of the panel session, just reminder that this webinar is being recorded, and the link will be available on our social channels.

So let me start a little bit by setting the scene. I think we can all agree that the Clean Energy Transition is now unstoppable. Energy from wind is growing around 10% annually, adding an extra 80 gigawatts per year. Solar energy is forecast to be the world’s largest sole source of electricity by 2027.

Furthermore, renewables are known to be by far the cheapest form of energy for the future. So, the solid economics of solar, and the heightened need for energy security in a world that is beginning to look more and more scary in return for geopolitics and conflicts. And growing protectionism makes it difficult, we think resists this already progressive path. I think most people would agree that it is a good thing. It’s a major contributor, of course, to our race to compact the biggest issue our time, which is climate change, and the effects of climate change on many of our populations.

Our young people are experiencing the greatest anxiety ever recorded with more than 60% of people under 18 claiming to have climate anxiety. But despite this positive outlook, and we should all be optimistic, the industry is not without its shadows. And by “we” I mean, we the industry, our elected Parliament’s and our citizens all face the uncomfortable reality that there are some challenges that we need to address are trade-offs.

Let me just mention a couple of those. One of those tradeoffs is energy independence versus reliance on China. We are being supplied by vast amounts of cheap solar modules, for example, from China, which is a good thing for households wanting to invest in solar and to reach our goals for net-zero. The biggest costs are now installation, but it is not such a good thing for Western businesses who are facing challenges to stay afloat amongst these cheaper imports. The USA tariffs on renewables are up to like 40%, but still are cheaper than those that can be produced in that country.

Another tradeoff; net zero emissions versus the potential of unmanaged adverse impacts on people and planet further up the supply chain, renewables a massive contributor to our national goals to meet the net zero course. But there are metals and materials needed to manufacture those modules. And those do not come without some risks that need to be managed.

So, the world is committed to coming out of hydrocarbon, we are moving out of an oil era, but we are moving into a new age of minerals. So, to put it plainly, the clean energy that we aspire to generate and power our houses and our businesses will provide an estimated 3 billion tones more of metal to produce the clean energy that we need. So, for purchases and producers of clean energy, there are some key priorities that they must do to facilitate this path to a cleaner future, but also to manage some of those challenges.

First, we have to ensure that production of clean energy technology doesn’t harm people and the environment – the unintended consequences. And that generating the energy to produce these inputs into the materials that we use them. The machines and equipment that we use for clean energy do not eclipse that vantage by creating more greenhouse gases in its manufacturing processes.

So, these are the ESG, environmental and social governance risks that supply chain managers and procurement teams must address routinely. And as well, the regulatory burden is mounting in response to this in response to civil society’s alarm around some of these risks, and we can see since 2010, when the Dodd- Frank Act in the United States was first enacted to really kind of raise alarm.

Companies need to be more cognizant of the potential of conflict minerals in their supply chain, as the impact has grown exponentially, and this is no longer something which is going to happen in the future. This is happening now at the end of last year, and companies are having to report and demonstrate that they reacting when they find risks in their supply chain. So, with that background, we wrote the material change for renewables report, which was for the water electronics industry. But we thought it would be good to update this and focus it on the renewable sector directly.

So, with that, I’ll hand over to my colleague, Zandi Mayo, who is going to talk about some of those ESG risks, and some of those materials that we have identified thar are prominent in the supply chain.

Zandi Mayo

Thank you, Assheton.

So, in material change for renewables, we approach environmental, social and governance risks by analysing 22 ESG issues. And we think that these issues are important because they give an accurate set of indicators of supply chain risks, that companies are being asked to analyse, monitor, and take action to avoid.

So, to assess these ESG risks in solar and wind supply chains, we look at the strength of association of these twenty-two ESG issues with the production of the 17 minerals and metals. And by strength of association, what we mean is the likelihood that these materials could be linked to these issues. So, we chose the seventeen minerals and metals as they are key to the production of solar panels and wind turbines. And because they form the main composition of materials needed to produce these technologies, they are predicted to meet future demand for materials needed to produce them.

Looking at this matrix which provides a summary presentation of our main findings, we see that the ESG landscape is complex and that the ESG issues are not confined to a few topics. There are many issues in the supply chains that producers or buyers of renewable energy technologies should be concerned about. And a few that jump out are (because they have a high likelihood of being found in production of many of these materials) pollution and negative biodiversity or conservation impacts, as well as many social issues such as company community conflicts and child labour.

So, while we tried to present this in a way that is pragmatic and easily understood, but it’s also backed by robust data, there’s a lot to think about. And looking at a generalised overview of a single point data for risk mitigation might fail to understand the context and provide meaning for decisions. So, to provide this context, and help the user understand what they should really be aware of, so they can act, we provide profiles on three key materials aluminum, steel, and silicone. And we selected aluminum and steel for the key roles they play in both wind and turbine solar panel production. And silicon we selected due to its importance in solar panels and the topicality of ESG issues associated with its production.

So, what is important to know about aluminum?

First, we can look at the supply chain aluminum comes from a rock called bauxite, which is then turned into alumina and eventually into aluminum. It’s used in the case of renewables for supporting structures and frames, for casing components and for wiring. And there are different ESG risks in various parts of the supply chain that we need to consider. At the mining end, bauxite is often found in shallow deposits, which means quite a lot of surface area needs to be taken away to get up the Bauxite rock and it typically is mined at in an industrial scale. So, what you will find is that bauxite is often associated with deforestation, loss of biodiversity and degradation. And when this happens, there’s also a possible link with the displacement of and disruption of indigenous people and local communities. As a lot of these mining areas are remote and located in areas where indigenous people have their territories. So, recent reports have linked bauxite mining with human rights and company community conflicts such as in parts of West Africa and Brazil.

Also at the mining stage, we find that the alkaline residue produced by bauxite mining can be highly polluting if it leaks from storage lakes. But another thing to consider and know about aluminum is that to convert bauxite into alumina, and alumina into aluminum takes a significant amount of energy. And about 80% of this aluminum is processed in China where it is powered by coal fire.

So, for these reasons, we see that greenhouse gas emissions have a strong link with aluminum. And because of this, the aluminum sector is responsible for about 2% of global greenhouse gas emissions each year.

And you tend to find that some companies are relocating to places where there’s growing amount of hydropower energy available. But the good thing about aluminium is that it’s highly recyclable and its recycling rate has gone up, although there is still room to grow.

Let’s look at steel now.

Steel is mined from iron ore and is then typically smelted to produce pig iron, which is then refined to produce steel. And it’s used in solar and wind technologies for supporting structures for building foundations and casing components in wind turbines. While steel is linked with similar ESG issues as aluminum, the production of iron ore is not inherently more environmentally or socially harmful than most other types of mining. But what we see is that the sheer scale of iron ore mining with more than 917 Mines operating globally means that negative impacts are more widely reported, and in comparison to aluminum, just to put this into context, we see that 23 times more iron was produced in 2022, then aluminum, so that’s 1.6 billion tonnes of iron ore.

There have been several high-profile events related to iron ore mining in recent years, which have caused media attention. To name a few, this includes the collapse of a tailings dam in Brazil in 2019, which killed 270 people and released a toxic mining waste into soils and waterways. And in response to this disaster, the global industry standard for tailings management of shoring system was developed, and a global database of tailings dams was established. But another example of this is with links to indigenous peoples’ rights violations, an example that comes to mind as the widespread outrage that came after the destruction of the Dukane gorge cultural heritage site in Australia in 2020. And this was a sacred site for the Kurama indigenous peoples.

But the good thing about steel and most of the salient issues that occur at the local level is that they can be mitigated by strong Mindsight management systems. Although this isn’t always the case in practice, but further along the supply chain, another thing to consider is that we find steelmaking is linked to greenhouse gas emissions. And this is because iron is most commonly smelted in coal burning furnaces.

And to add on to this further, carbon emissions are released when carbon and pig iron is removed to make steel. But overall, we see that iron and steelmaking makes up to 9% of global greenhouse gas emissions. And again, we see that this production in China has a massive influence on greenhouse gas emissions, or steel, which is why China is now pledging to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions from its steel industry, aiming to be carbon neutral by 2050. And they plan to do this by shutting down the most outdated and polluting plants. However, this could have impacts for this for the supply of steel in future.

But moving on to the last profile that we took the dive into in the in the report is silicon.

When it comes to silicon, the strongest association with ESG issues occurs at the manufacturing stage, rather than the mining stage unlike most mined materials. Here, we see that for savers the critical ESG issue to consider which reflects the numerous reports of forced labour rights issues in polysilicon manufacturers in the Xinjiang region of China. Just to look at the supply chain polysilicon is a form of elemental silicon made up have small interlocking silicon crystals, and it is an important input material for photovoltaic cells and solar panels. Some public reports that claim polysilicon manufacturers in Xinjiang either participate in Chinese government labour displacement practices or are supplied by companies that do so. This is why we see legislation trying to address this such as the wage or forced labour act in America and other forced labour laws that are coming up in Europe.

Another important thing to know about Silicon is that while only a moderate association with greenhouse gas emissions is currently found, studies predict that these emissions could rise sharply in the coming years as solar panel production ramps up. So, our analysis of these three materials and summary analysis of the seventeen materials shows that the ESG landscape is not limited to just a few topics but is complex, and there are multiple ESG issues in the supply chains that procurement managers should be concerned about.

So, how should companies respond to these? I’m going to hand it over to Sol to talk about this.

Soledad Mills

Thank you, Zandi.

As Assheton and Zandi have highlighted, the regulatory burden associated with responsible sourcing is growing at pace. And while some regulations are selective about the minerals they cover and ESG risks that companies are required to disclose on and report on, new and emerging regulations like the CSRD the corporate sustainability reporting directive, and the corporate sustainability due diligence directive or CSDDD are often far broader.

So, to source responsibly, companies should take a comprehensive view, and seek to identify, avoid, and address potential and actual adverse ESG impacts.

Setting up a supply chain due diligence management system involves several key steps. The first step will be to define the objectives of the due diligence management system, including ensuring compliance with regulations, mitigating risks, promoting sustainability, and upholding ethical sourcing practices. It may also involve engaging with stakeholders including customers, investors, suppliers, employees, NGOs, external partners, and experts to identify expectations regarding ESG issue relevance and performance.

The next step is to develop clear policies and procedures outlining the requirements for due diligence, supplier assessment, monitoring, and reporting. Establishing thresholds for conducting additional or enhanced due diligence where risks are identified will help companies to target limited resources towards high-risk supply chains.

Engaging with suppliers to communicate ethical sourcing practices and expectations throughout the supply chain is essential. And to understand risks associated all the way upstream, it is important to cascade requirements down the supply chain and establish visibility and traceability to identify the country of origin of raw materials.

At the same time, companies should conduct a comprehensive risk assessment of their supply chain to identify potential risks such as human rights violations, labour issues, environmental impacts, and corruption, all of which is now a part of many mandatory due diligence regulations. Companies need to carry out due diligence on suppliers to verify their compliance with relevant regulations and standards, which could include for instance, researching company history and ownership, reviewing documentation, sending questionnaires, conducting site visits, and engaging with stakeholders.

Companies should define the frequency of due diligence to regularly assess supplier performance through periodic reviews, questionnaires, and audits. Any identified noncompliance issues should be addressed through remediation measures such as corrective actions, training, and capacity building initiatives.

Companies need to establish mechanisms for reporting and transparency including regular reporting on supplier performance risk assessments and compliance status which is also a requirement of the CSRD.

And lastly, it’s important to continuously review and improve your supply chain due diligence management system based on feedback, lessons learned, and changes in regulations or industry standards. Industry or multi stakeholder voluntary ESG standards and frameworks reflect and can also help companies anticipate this broadening of ESG issues of concern and expectations of supply chain due diligence. In the report, we have published a matrix of voluntary standards that provides coverage of a broad range of ESG risks relevant to the mining of minerals for wind turbines and solar panels. By encouraging suppliers to adopt these comprehensive standards, producers and purchasers of clean energy can have some assurance that the company has been verified for their management of performance on prevailing ESG issues.

The matrix also includes some issues specific standards that are more in depth in their requirements and focus on particular ESG areas. The two new standards are the Solar Stewardship Initiative’s ESG standard and Equitable Origin’s standards for renewable energy development.

The draft E0100 standards for wind and solar were launched last month and are the only comprehensive standards specifically designed for the evaluation of ESG performance at renewable development sites and their supply chains. We’ll hear more about them from Jennifer Turner at Equitable Origin as part of our panel session shortly.

Some of the tools that can support risk identification and management include TDI Digital’s online platform, which can help companies quickly identify those standards and regulations most relevant to their sourcing operation conditions, and ESG risk exposure. The integrated compliance assessment tool can be used to benchmark a company’s own standard and quickly compare multiple standards simultaneously.

Finally, producers and purchases of clean energy can support responsible sourcing by engaging directly in initiatives that seek to improve environmental and social conditions upstream, and to promote responsible procurement of clean energy. For example, the Fair Cobalt Alliance works with small scale producers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo to improve conditions in cobalt mining areas and is directly supported by companies throughout the supply chain, including Tesla and Google.

The Solar Stewardship Initiative (SSI) was established by Solar Power Europe and Solar Energy UK to enhance transparency and promote responsible production, sourcing, and stewardship of materials in the solar value chain. The Solar Stewardship Initiative works with manufacturers developers, installers and purchasers across the global solar value chain and is currently becoming a multi-stakeholder initiative.

Clean Energy buyers Institute’s beyond the megawatt initiative seeks to maximize the environmental and social outcomes of the Clean Energy Transition, by leveraging the influential demand of energy customers through the procurement of clean energy that is resilient, equitable, and environmentally sustainable, and they have a few tools on their website to help clean energy purchasers conduct due diligence in their supply chains.

As has been the case in other sectors, the greatest impetus for change builds when companies with a common purpose such as buyers of clean energy, act collectively, coordinated action and ESG expectations from buyers can ensure consistent messaging to suppliers, and allow buyers resources to be pooled to target improvements more effectively, which in turn, ensures that suppliers can more easily and efficiently demonstrate how they are meeting buyers ESG expectations.

Now I’ll hand it back to Assheton to take us into the panel.

Assheton Carter

Thanks, Sol and Zandi, that is great.

You managed to give us a glimpse of the vast amount of data that is out there on ESG and circumstances in the mineral supply chains. And I think one thing, which is always difficult to do in a short panel like this, is to demonstrate how we can make sense of that through the systems that we build, and to provide that context.

And so, as Zandi tried to, in the time available, talk about the context of these things, because of course, a single point of data does not give you the whole story, we need to contextualise that.

In our report, we’ve identified many different certification systems which cover these supply chains. But the number of different frameworks that are out there are vast.

Another thing that we are very dedicated to at TDI sustainability is making sure that we have a way to demystify which ones are those that do apply in our Integrated Compliance Assurance tool.

For those of you who are viewing, just in case you have not noticed at the bottom of your screen, there should be a Q&A tab. Please do go on there and post your questions and we can address them to the different panelists, which is a nice segway to bring on the next panelist, Jennifer from Equitable Origin.

Jennifer Turner is the Energy Director at EO.

So Jennifer, Sol mentioned EO, tell us about Equitable Origin, and in particular, the new standard, which is out for consultation now on wind and solar.

How does that fit in?

We’ve been talking a lot about supply chains and metals and minerals. But Equitable Origin is at the other end of the supply chain. Please tell our participants a little bit about what you aim to do and how it can change their lives.

Jennifer Turner

Absolutely. It’s wonderful to be able to join this discussion today and take part in this important conversation.

A little bit of information, I’ll start more broadly with Equitable Origin and why we do what we do. So, we are a nonprofit and our mission is to partner with a broader set of stakeholders to collaboratively work towards more responsible energy development and to drive improvements in a field that can often be quite problematic.

Equitable Origin was founded back in 2009 and spent a full three years developing our first standard, through engagement with many stakeholders and rights holders. And we have been iteratively building on that ever since. And so, coming back to why this is important. Assheton, I really liked how you opened with talking about the unintended consequences of resource development, which I think are ubiquitous and across the board, many of the same issues that we are seeing in oil and gas are being replicated, yet unseen, with renewable energy projects.

And another thing that kind of common, a common tie, that I think extends to all of these developments, is the urgency with which we need to create change. There is a dire and urgent need for that. And when we think about how to achieve that, I don’t really think it’s possible until we have a system that we collaboratively contribute to, that offers a line of sight in a way that’s connected to the impacts that these projects have on the ground and that recognise companies that are engaged in better practices.

And so, in that way, it’s our hope to make better practices more competitive and generate better outcomes. Throughout a project’s life, this part is important. In a way that is tied on an ongoing basis to impact or input from impacted communities themselves. It is personally important to me, so I speak from extensive experience here, I’ve spent over a decade working on drilling rigs in Canada. And, we are known to have some of the highest standards in the world. And yet, I’ve almost died. I have known people who have died in this work. And so, it was noticeably clear to me then, that resource development is tied very deeply to human rights issues and abuse in a way, and I appreciate how you raised this Assheton, in a way that is so unseen. That really does tie into the importance of certification, and an approach that comes as close as we can to seeing that full picture.

So, coming back to the draft standards for wind and solar, we have talked about some commonality in these issues, we do have the same core principles that guide all our work at Equitable Origin.

Within these five principles, we’ve got community engagement and human rights, indigenous peoples rights, occupational health and safety. And to build on Zandi’s remarks, it is absolutely true that indigenous communities in particular, I think, have expressed frustration with a lack of recognition for indigenous rights, and the related expectations for engagement and partnership building, relationship building with communities. It’s not just a challenge, but when we think about how to develop these projects better, these projects themselves would benefit from a better understanding of cumulative effects pathways, a more holistic view of the impacts of development.

We talk a lot about regulatory compliance and regulatory pathways, but I don’t really think there is much recognition for indigenous lead cumulative effects assessments. And that can only really come from ensuring that those perspectives are integrated directly. So that is why we see an important role in certification, and collective intelligence really defines what is better and what isn’t.

So, coming back to our work and wind and solar, this is only as strong as everyone that comes to the table to collaboratively build it. So, I would like to thank many people here, as we’re about five weeks into an eight-week consultation period, it’ll end on May 31st.

One of the things I think that makes EO special is that collaborative framework and multi-stakeholder focus, and our standards do reflect this.

If you are interested in commenting or contributing, that would be wonderful. I would like to introduce Kaki Comer, who has done so much work to really take leadership with the development of our technical supplement in wind and solar. She is here at this event and will be adding the link to the draft standards for your review, providing an opportunity for feedback right in the chat. So,there is my plug, and I hope I’ve covered the answers for your questions,

Assheton Carter

As always, very well, indeed. But let me ask a couple of follow-up questions here.

What many people might not know about EO, is as well as the standard work that it has been doing, it also works a lot in the field with indigenous peoples too. In fact, it was built around that multi-stakeholder and very inclusive model you mentioned.

And you mentioned that the Ecuador origin has been developing these standards since 2009.

So, let me try and collapse kind of two questions into one, when you’re convincing companies to come on board and adopt the EO? What is the business case? What are the benefits that they can see from a standard like EO in particular? And similarly, when you’re talking to indigenous peoples and communities around renewables gas projects, how do you convince them that this is going to enable them to hold the developers to account what is their business case?

Jennifer Turner

I’ll start with communities first, because I want to start with what I consider to be more important. Communities are naturally, I think, apprehensive of any group or entity that is, in this space. There are a lot that are directly tied to resource development. This is especially true for indigenous communities. And I think we have gotten a little bit of a reflection here today, but you know, it is worth getting a deeper understanding of it. There are many excellent reasons for that. The same principles that we aim to uphold and external stakeholders, we really try to turn the mirror back on ourselves and uphold them internally as well. We work to really, you know, engage in relationship building, and work towards partnerships. In an indigenous space and in indigenous communities, I don’t rely on people to trust what Jen Turner or what any of us say about Equitable Origin, or the value of that. That’ll ultimately to be defined by indigenous communities themselves, and indigenous leaders themselves, who are engaging in that process, are seeing how their communities can have an input into a framework that gives them a direct say, into what is better versus what is worse, versus a better that is kind of defined from the outside in.

You know, a bank in London that does not really integrate their perspective or the impacts that they’re facing on the ground. For companies, I think companies that are really in already engaged more in sustainability and looking for a way to authenticate that story and prove that story, which is, I think, from the outside looking in very difficult to differentiate from greenwashing. So then how do you tell the difference? And that can only really happen through some form of external and independent assessment that is transparent and accountable and publicly visible. The framework for that, by definition, if it is going to work for the public, it can only really be collaboratively built and tied to this kind of community input. You know, if we do that correctly, and get recognition for it, which I think is really starting to happen, I think this is how we win together. We ensure in the process that better practices become more recognised, more competitive, and hopefully drive better outcomes in a world that so sorely needs it.

Assheton Carter

Perfect. The trust deficit is something we’re going to have to overcome if we’re going to find a sustainable path forward for these much-needed developments. But thanks very much, Jen. I’m sure we could go on speaking for many hours on this.

Let me turn to Zandi. thank you for the presentation of the report where we took some of those materials and try to identify and present in a coherent comparative form, the ESG relative associated risks associated with them. But of course, these aren’t the only minerals and metals that supply chain managers must procure for their renewable projects. What are the other metals? And what is what how, how should we be focusing on those? Or how would you advise our viewers to focus on wherever they go to find this data?

Zandi Mayo

Thanks, Assheton. Yes, so we singled out those seventeen minerals and metals that we presented in the matrix, as we think they are the most important and are a good place to start for companies. Looking at the findings, we can see that some of the materials other than the three materials that we presented profiles on, have links with many ESG issues, and to name a few, copper is one that jumps out as it has strong association with many environmental and social issues, and is used in both solar panels and wind turbines.

Another one is tin which is used in solar panels as a key material to pay attention to in terms of the supply chain risks that come up. And we can also look at cobalt, which is found in wind turbines, and scores high across most of the ESG issues that we assessed and has also gained a lot of attention in media. We have detailed profiles on all these seventeen materials we presented like the ones on aluminium, steel and silicone. While this report only focuses on minerals and metal supply chains, some other important materials that are worth paying attention to are plastics and glass, which are also key to solar panels and wind turbines. And we also have profiles on these, but we’ll see an importance of plastics producing the circularity regulations and single-use plastics and in organic materials are also coming into the forefront of stakeholder’s minds because of this. There are many other materials in solar panels and wind turbines that TDi maintains a database of, and we have a database of over 50 materials.

However, looking ahead, as you mentioned, there’ll be a big number of materials needed to increase production needed to produce these technologies. So, we should think about where this will come from. And the sources could also be a source of risk. For example, considering that there are trillions of tonnes of materials in the deep-sea environment, and that there are already 30 concessions in the deep-sea, half of which are owned by China. This could be a potential area for risk that would need to be considered and TDI is also keeping an eye on.

So yeah, we have these databases and we’re also planning to launch our risk assessment mitigation tool on our risk platform that can provide valuable insights to companies.

Assheton Carter

Great, thank you. Feels like it’s going to be a never-ending list, which is almost kind of parallel to the never-ending list of regulations and ESG frameworks that Sol touched on and some people refer to as a kind of alphabet soup. So, we care about these things because we’re mindful human beings. But as a company, we also have to respond to these regulations.

So, if you’re a supply chain manager, and you have got this barrage of the tsunami of regulations and ESG frameworks coming at you, where do you focus? What is the most important thing? Tell us a little bit about how you can help them navigate this – this forest of regulations that is growing around us?

Soledad Mills

I think the CSDDD is kind of that meta regulation, because it establishes far-reaching mandatory human rights and environmental obligations on both EU and non-EU companies that meet certain turnover thresholds. And these obligations will start from 2027, they apply to a company’s operations and those of its subsidiaries and to those carried out by a company’s business partners in its chain of activities both upstream and downstream.

So, it is a very broad scope. And the human rights and environmental obligations include what we’ve been discussing, integrating due diligence into policies and management systems, identifying and assessing actual potential adverse human rights and environmental impacts, implementing measures to prevent or minimise those impacts, monitoring and assessing the effectiveness of those measures and providing remediation to those affected.

Another one to highlight is the EU Forced Labour Regulation, which was just passed by the European Parliament, and prohibits products made with forced labour from entering the European market, which could have a significant impact on the solar industry. Lastly, the new EU deforestation regulation will impose due diligence obligations from the end of this year, aimed at tackling deforestation and forest degradation. You may wonder why this is relevant for renewable energy supply chains. As Equitable Origin highlighted in a recent art article, there’s a race for balsa wood for wind turbines, 80% of which comes from the Ecuadorian Amazon, and has led to growing problems of illegal logging, violence and negative impacts on indigenous communities.

So, it appears that the regulatory burden will continue to grow, and it means that there’s an increasing need to fully understand the entire supply chain of renewable energy products all the way down to the raw materials and where they come from.

Assheton Carter

Thanks. I started this webinar, making the remarks that we’d be optimistic, but I didn’t know Zandi and Sol’s views have made me lose my mind having heard about the complexity of the supply chains of things we’ve got to figure out.

But maybe we can get some support on that. I want to open the floor to questions. We’ve already had three questions now from the Q&A box, please keep adding to those and we’ll try and address those. Now, I’d like to invite now to join us, Joel Frijhoff from Orsted who knows exactly how to solve problems because at Orsted he is responsible for sourcing. I wonder if you can tell us a little bit about yourself and Orsted, and how to manage complexity along with your insight.

Joel Frijhoff

Thank you Assheton. And thanks, TDi for the invite. I’m very happy to represent Orsted on this panel on this very important topic. So, I represent Orsted, which is the largest leading offshore wind developer globally and we have operations in the US, EU and APAC. I work in our Global Sustainability Team as a Sustainability Due Diligence Manager where I am, amongst others, leading our work on the metals and minerals program as we call it.

It has been a program which has been in place for around three years. And I was asked to share a bit of the challenges that we have on those and maybe highlight only three and how we try to overcome those challenges.

I think the first one is a clear lack of maturity on the topic in the renewable energy sector, I always say we are the last sector to take a seat at the table to dip our toe into these existing supply chains of key metals. And we are trying not to set up new supply chains for these metals, but rather steer a tanker in the right direction. And that lack of maturity is among my peers, but as well as with our suppliers, is kind of holding us back a little.

The second is a lack of supply chain transparency, not knowing, or at least having gaps in information where these materials originate from, they are extracted very deep into our supply chain.

We as an end user are not involved in direct purchases of these metals. And obviously not knowing or not having that transparency makes it very hard to map and then subsequently address human rights impacts.

The last one is lack of leverage. I mean, even if you look at the global markets of the three metals that were presented, and also the ones in TDi’s report, these metals are used globally in different sectors. If you take the share of renewable energy sector that is already a small, small share, if you then take even as a leading offshore wind developer globally, it’s still a very small part of the market that we represent for steel and copper, for example, that end up in our renewable energy projects, making it very hard to facilitate change. So not only thinking about the challenges they will have, but how do we try to overcome that?

One of the key things we’ve tried to do with this is mature the topic with our direct suppliers, just to ensure this conversation on sustainability topics that we have with our first tier suppliers and try to push them towards mapping their supply chain. That is what we try to do at the individual stage. But also reflecting on some of the comments that were already made, we also seek active collaboration with others.

We do that as an end user in something that’s called the Dutch renewable energy covenant where we work with some of our suppliers, other developers, as well as civil society and Dutch governments on this topic, and that’s all that we do on our side of supply chain. But we also want to educate ourselves on what does responsible mining actually means.

At the end of 2022, we joined the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA) we joined IRMA because we consider that as the most comprehensive standard, they publish all their assessment reports publicly on their website. It’s a truly multi-stakeholder initiative. And one of the key points as well as they host a buyer’s panel, which allows us, as of yet, unfortunately, the only renewable energy company being a member of IRMA, but it does facilitate those dialogues with, for example, the gemstone sector, the automotive industry and the electronics sector to try to learn from them.

We’re trying to not reinvent the wheel, learn from their challenges, their opportunities, and then jointly trying to push this agenda forward. I’ll pause there and go into more detail if there are any questions on that.

Assheton Carter

That’s great. Thanks, Joel. And I agree with you that this is such a complex topic now. There are so many interrelationships, and I think one way is to fail is to try to do this alone. So, we have to reach across the borders and boundaries to other industries and players as well. I guess one kind of final comment before I move to those questions in the Q&A box is, you’ve been doing this for a while not just in Orsted, but also in other companies, your previous employers. It’s a new industry and many new people are coming into it. What’s your one piece of advice? I mean, might now be to read this excellent report. But beyond reading the excellent report, what would you advise your new incoming Supply Chain Manager and Compliance Officer to do to help them navigate this?

Joel Frijhoff

That’s a great, great question. I think it’s also on the minds of very many of the actors in the renewable energy sector. Besides obviously reading the TDI report, I think one of the key things is to just get started. It’s a very low maturity topic at the moment. It can be quite a challenge, but at the same time, there’s a lot of low hanging fruit.

I think seeking collaboration with others. Start talking about this topic with your with your suppliers, that’s only going to set you up for compliance with that upcoming law regulation, that you present it and action at the start. But it also positions you in a in a truthful manner as a front runner if you want to mitigate these actions, just we have been getting questions from NGOs, but also investors around this topic. And I assume we may be one of the first companies receiving these questions, considering our size as well, as well as our position in the market. But I cannot imagine we’re the last company to receive these questions around investors. So talk to also join if there are any investors on the call started including these questions in your in your dialogue with the companies in your portfolio, because in my opinion, this is only going to be a topic which is will be maturing over the next coming years and makes it so important that the company start started including this topic in their sustainability programs.

Assheton Carter

Right, thanks, Joel, just getting to some of the questions that come in. There’s one for Zandi here, which is about the data. So, the questionnaire kind of points out or has noted that our report, the TDi report is very much data driven. We seek out these saliency data or we seek out the data and we do our sentencing methodology. But is this data evenly distributed? Can we get equal amounts of data for all these different materials and against all the different issues that we’re trying to analyse and communicate?

Zandi Mayo

Thanks, Assheton. That’s a good question. It also ties into the previous question asked about how we verify reports of accusations such as in the Xinjiang region. This topic is complicated, because it is not always easy to get access to accurate data. And this is something we see with forced labour and the tricky thing about forced labour, is what we call a hidden risk. And it can be difficult, even if you do site audits to understand where there is forced labour. So, yes, for failure is one of those risks that it’s difficult to gather data on, especially when you are looking at looking at historical instances to base your dataset on.

What we try and do at TDI is not only look at the reports of instances that are coming in, but also look at predictive analytics and try to identify the situations where forced labour is most likely to happen. This could be based off various indices or indicators, such as in countries where there is a lot of migrant workers, or where the type of business activity needs to meet tight deadlines, or in countries or areas experiencing poverty. This is also a similar issue for child labour. Another thing is, when we’re putting together this comparative matrix of data, you are sometimes comparing different data sets and we take a lot of care at TDi to normalise this data and verify its accuracy. So, this doesn’t mean that they all follow the same methodology. Instead, it means that we make sure that the methodology is appropriate, and the risk can be singled out and compared.

Assheton Carter

Great, thanks. I think this thing about predictable Analytics is a thing because you know, we can’t go forward if we are always looking in the rearview mirror. So, we are trying to understand where the hotspots or risks are going to be in the in the future, and that is where we need indicators and indices to identify the circumstances where things might go wrong, so we can build that into our that into our decision making.

One of the questions which has come up here is that the participant is representing a company which is a developer in the UK and in Europe. They are thrilled to have this information to make their life more complicated and make their supply chain riskier than they thought it was to begin with. What do they do now? And, you know, there is a lot of talk about risk-based due diligence, which is an accepted and a path forward, what does that mean in reality? And what are your reflections on this question regarding what do you do with all this valuable information?

Soledad Mills

Risk-based due diligence is really the way to try to narrow down the approach and target resources on the higher-risk suppliers. So, what does that mean in practice? A risk-based approach to supply due diligence involves assessing and prioritising suppliers based on the level of risk they pose to the organisation in terms of compliance, reputation and sustainability. So, rather than applying the same level of scrutiny to all suppliers, a risk-based approach allows organisations to focus their resources on suppliers that present the greatest potential risks.

The first step is what we already discussed, conducting a comprehensive risk assessment of the supply chain to identify those potential risks, this might consider factors such as geographic location, industry sector, regulatory requirements, past performance, and potential impact on the organisation. Then companies can prioritise suppliers based on the level of risk that they pose to the organization, but also to people and planet which is the concept of double materiality and key to the CSRD.

High-risk suppliers may include those operating high-risk regions. TDi has a has a map of conflict affected in high-risk areas. There are other maps available to help companies identify what those high-risk regions are. They could also identify industries that have a history of noncompliance or are known to have worse ESG performance with suppliers that have a significant impact on the organization’s operations or where the company is more reliant on that particular supplier and substitutability is difficult.

Then the criteria for conducting due diligence on suppliers can consider the level of risk associated with each supplier. High-risk suppliers may require more extensive or enhanced due diligence such as site visits, assessments, third party audits, while lower risk suppliers may only require basic documentation, review, and ongoing monitoring.

Once risks are identified, the due diligence process can be tailored for each supplier, which may involve gathering additional information, conducting deeper investigations, and implementing risk mitigation measures that are based on the results of the risk assessment. And these strategies for mitigating risks associated with high-risk suppliers could include for example, implementing corrective action plans, providing training and support, establishing contingency plans to address disruptions in the supply chain, and, if no improvement is achieved, then potentially severing the relationship with that supplier.

And lastly, the frequency of the ongoing monitoring of high-risk suppliers obviously should be increased to follow up on mitigation actions and identify any changes in risk over time. So, by adopting this type of risk-based approach to supplier due diligence, companies can allocate their resources more effectively, and focus on mitigating the most significant risks to ensure compliance with regulations and ethical standards throughout their supply chain.

Assheton Carter

Great, thanks. A similar question for you, Jen. A bit of a cheeky question, I think. The developers have a lot to figure out, just trying to get their permits to get their wind turbines or their solar stands. Is there a supply chain requirement in the standard? Do you also require that they look up their supply chain? How do you kind of complete the system in terms of that element?

Jen Turner

We do have some supply chain requirements in the standard, and I will come back to saying that the power of the standard and how it is iteratively built over time, through contributions from a broader set of stakeholders. But really, I think the morecrucial pointt here is to envision how these pieces fit together.

I think it’s generally important to know that all of us here, I think we are just at a point where we really have to look for ways to co-create new approaches that do not replicate past mistakes. And so, to a certain degree, even when they are, let us say, perfectly built, I feel like there is an inherent limitation to frameworks or reporting frameworks, any version of even a standard or a target.

Any top-down approach, a certification tool, is good here, because it can help fill a gap in that because it’s tied to collective action, that is more bottom up or community driven, reflective of impacts on that scale. You know, this is where it can integrate, the upstream on the scene, you know, because I do like your comment on that Assheton, are those impacts are often unseen and unrecognised.

And so when we connect that scale, to these more kind of, I would say top down approaches, and that, you know, and we can kind of bridge this together when we see developers and buyers collectively back, a set of siting and supply chain requirements, that is more of a coordinated effort, and tied to those, you know, community impacts on the ground, then I think we have a framework where it’s like an ecosystem where these pieces fit together, that is tied to a greater leverage, and certainly more positive impact than any of us would ever be able to achieve otherwise.

Assheton Carter

And you told us a lot about what really counts is the communities and indigenous peoples and of course, EO has been dedicated to that. One of the questions here in the Q&A box is, how feasible is it to have workshops with communities within the context of the standard, to help them contribute to the knowledge around what is really a risk? I mean, the risk is, when we’re talking about risk, it’s about risk to the communities, how can they contribute to the design to minimising risks in development, and how can that be incorporated into the standard?

Jen Turner

There is always room for us to do more, but without that collaboration and relationship building, and input from communities, in my mind, this doesn’t work. And so, if you don’t have that line of input, and that relationship, I’m not sure if you have a full view of impacts anymore. So, this does require community engagement on an ongoing basis.

We’ve got this amazing team in Latin America, that is working with communities in the most beautiful way, we have indigenous communities in Canada that are hearing about that, and saying, “Oh, wow, you know, like, we see this”

We feel this common driver here has these deep ties. And this makes us want to engage because communities are limited in their capacity. And so, they must, they have to kind of pick and choose. And then we have indigenous communities and tribes in the US that are looking at both of these ends, and saying, “Well, how can our rights be more recognised?” You know, be it by the state, be it by the feds. And so, really, this comes back to my point about connective power, and moving together, all of this becomes so much more powerful. And so, on that note, I do not really think we can afford to not engage, or at least build relationships with communities. And so, we have that greater collective intelligence that we can build these things on.

Assheton Carter

That’s great. Thanks. And I think I am very much in need of a greater collective intelligence in my life. Before I close, I’d like to kind of throw the last question that Joel – we talked a lot about kind of standards, and you mentioned that you your company is committed to IRMA regarding the mining and the processing, and supply chain standards, or chain of custody standards. There are quite a few standards that there’s Zandi and Sol mentioned that we have analysed. We keep a database of over 200 different standards and try and make sure we compare them. Is there a risk here that if we pick only one standard, we will cause friction within the industry and supply chain? And is there room here for cross recognition or harmonisation of standards without having to without having to select the winner or play God over which standard is best?

Joel Frijhoff

Great question. I mean, before joining them, obviously, we made a comparison of the different standards. And one of the key reasons for us to join IRMA that I already mentioned was the transparency around assessment results, it wasn’t really mentioned we needed we needed transparencies, our stakeholders, as well as those are those around the mining company need to and deserve those, that transparency around the assessment results also to hold mindset accountable. Other than that, obviously, that that bias panel that I mentioned, facilitating that increase in leverage that joint discussion around a topic.

You raise a great point around the around the cross recognition. I do think there is a plethora of mining standards out there. And I’m aware of the divergence around some of these mining standards out there globally.

I think there is a big need for convergence. For my part, from an end user perspective, I would like to mention that for us, there are some parameters that we consider that need to be met by such a mining standard. And those and those are, amongst others, the ones that I mentioned at the beginning, fully multi-stakeholder, already at board member transparency in assessment results.

In my previous job, I found out that there could be one of the one of the key reasons for critique towards the mining standard. So again, I do recognise your point, but I do think also as an end user, there are some parameters that we need to consider as a minimum that should be reflected in a cross recognition as well as in conversions of mining standards.

Assheton Carter

Right, thanks. And in another talk, it’d be good to explore what your standard is for the standards that you employ. But I think we’ve got to draw it to the end.

So perhaps you can gauge the concluding slides. But to thank the panelists, I feel I’d been on the journey right from the top of the supply chain, where we can find anything in a bauxite rock in the in the forests of West Africa, right down to developing renewable energy in the US and Canada. I think the conclusions we can draw here is that this is a complex picture, that there are many different facets of sustainable development in the clean energy transition, not least in the supply chain. And due to the regulations, which are coming down the road to affect and compel companies to pay attention, there are a broad range of ESG issues that we have got to better understand how to mitigate.

It is not enough anymore just to point to the halo around the clean energy industries, renewable energy industries, solar and wind. There’s also a responsibility here to recognise that we’re entering into metals era, and we need to acknowledge that that also comes with some tradeoffs and impacts that we’ve got to try and reduce.

And as I mentioned earlier, I think a short way to fail to achieve our goals is to act alone. This is far too complex. We have got to have relationships, strange bedfellows, if you want with, with companies in industries that we might not naturally do. And we need to really look at what in fact our systems are, which is now much more on the verticals up and down the supply chain rather than the horizontals, which is where you are located.

So, thank you all thanks for the listeners. This is a passion for TDi sustainability. We are building up our databases on these risks but more importantly on how to manage and mitigate those and contribute positively. So, thank you again, and the webinar will be recorded and is on the movie centers on our socials, and if you want to download the report, you can do so using the link.

Thanks very much, everybody, and we will see you next time.

supply chain

supply chain

Re-defining legacy | Supporting companies and investors in achieving positive legacies in mining operations

3rd July 2025 supply chain

supply chain

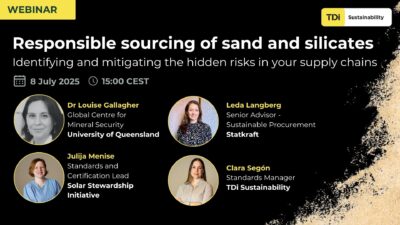

Responsible sourcing of sand and silicates | Identifying and mitigating the hidden risk in your supply chains

24th June 2025 supply chain

supply chain