Should we mine deep-sea minerals?

In May, TDi’s Dr Assheton Carter, took part in a panel discussion and spoke on deep-sea minerals’ extraction at the Cobalt Institute 2021 Conference.

In this piece, Assheton talks us through some of the key questions of the day. He offers his view on what can drive effective dialogue on this issue.

What are deep-sea minerals?

Between 3.5 – 6km beneath the surface of the Ocean there are billions of tonnes of nodules resting on the seabed. These are deposits containing manganese, nickel, copper and, of course, cobalt. It sounds like science fiction, but it’s not.

The source is significant. One estimate suggests there are 44 million tonnes of cobalt metal content alone in the Clarion Clipperton Zone. This is one of four vast areas known to have large occurrences of nodules.

We rely on cobalt in many aspects of our lives. Its use is highly topical right now as the fuel for our green economy. It is a critical mineral in the batteries that will power our fleet of electrical vehicles, cell phones, and other electronic devices.

Should we mine deep-sea minerals?

Scientists and businesses have been researching and testing the viability of extraction and processing since the 1970s. Considerable investment has been made into detailed studies in the last ten years.

The International Seabed Association (ISA), the body that governs the deep-sea and its minerals, has issued 32 permits to countries to explore the seabed. Developers including The Metals Company and the GSR Group have announced that they will begin recovering deep-sea minerals commercially from 2024.

But there are challenges connected to environmental, social and governance aspects of deep-sea mineral mining. And there is deep polarisation of opinions on whether the potential ESG impacts are acceptable when weighed against the benefits.

The question we need to ask is: can we source deep-sea minerals responsibly? And what is considered ‘responsible’ to investors, to regulators and to consumers?

What do opponents say are the challenges for deep-sea mineral mining?

In the last 4 months, WWF, Greenpeace, Amnesty International, and a group of Pacific organizations have all published reports or public statements. They are calling for a moratorium or total ban on deep-sea mineral mining. Brands including BMW, Volvo Group, Samsung SDI and Google have also announced support for a moratorium and refused deep-sea minerals in their supply chain.

Deep-sea scientists warn about negative impacts on unique and fragile ecosystems. One concern is the plumes of sediment created by the collectors. The plumes drift in the Ocean’s current, sometimes for kilometres. Scientists say they are likely to irreversibly harm the areas where they settle.

The nodules themselves are host to species about which is little is known or are as yet undescribed.

As one of our last wildernesses, scientists have talked about how this type of activity could make some species regionally extinct.

Also, many fear that coastal communities dependent on the ocean for their livelihood will have a negative experience of deep-sea mining.

What do supporters of deep-sea mineral mining say?

Proponents for deep-sea mining including contractors, governments and some scientists, point to the forecasted rising demand for metals. Can we afford to turn away from this new source of raw material?

They also argue the benefits of deep-sea mining in contrast to mining on land, which is not without its challenges. Mining terrestrially is energy-intensive and is a major emitter of greenhouse gases. It also encroaches into forests of significant conservation value.

Mining is a frontier activity, and there is opportunity to gather scientific knowledge and learn more about the biodiversity of the deep-sea. What’s more, developers come with the finance to support this time consuming and expensive activity.

There is already a great deal of work underway by some of the key contractors to assess the potential environmental impact. Their argument is that there are already impact assessment processes in place and regulations are being developed. Why turn back now?

What is the impact of deep-sea mineral mining on countries that rely on the industry for their economy?

There is no clear answer to this. But it is a question which we need to talk about with some urgency. The trade-off is complex. It is not only about harm or extinction of biodiversity in the places where cobalt is extracted. It is also about the benefits thousands of miles away on land.

We need to work out how to set up practical, achievable frameworks of responsible production and to measure the benefits. When we can do that, we can more easily make decisions and know where to put our energy and resources. At the moment, the debate is polarised. That is not the way to progress.

What next for deep-sea mineral mining?

First, we need to recognise the important part of this issue is about ‘responsible supply’ of materials and what this means for deep-sea mining.

Second, we need to ensure that players along the entire supply chain are informed on the topic. This includes metal exchanges to downstream manufacturers and investors. All parties need to have a voice. The opportunity to contribute to the discussion, must include every party and at an early stage. It is rare that we get an opportunity to really understand and consult on an industry before it begins. We should grasp this one.

While we better inform ourselves, we should learn from other parts of the industry that are convening dialogues. For example, the Fair Cobalt Alliance, and alliance of miners and traders, incl. Glencore, Huayou and China Molybdenum. There are also members that are battery manufactures and OEM, like ATL, Tesla, Signify, Fairphone, and Volvo.

Third, we need to create the space for dialogue, where all stakeholders have a chance to be heard. The International Seabed Authority has a mandate, a process and is piloting its consultation process. Not everyone is aware or familiar with that process, however.

In this highly controversial and heated topic, we are working with the World Economic Forum (WEF) to create an impartial space for dialogue. This is the WEF Deep-sea minerals dialogue. We hope our dialogue will help to stimulate measured discussion, and that other similar opportunities can be created.

I hope that we can find ways to come together, to form dialogues involving the entire supply chain. We must work collectively to address these significant sustainable development dilemmas that have generational implications.

supply chain

supply chain

Re-defining legacy | Supporting companies and investors in achieving positive legacies in mining operations

3rd July 2025 supply chain

supply chain

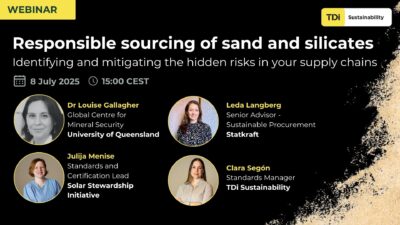

Responsible sourcing of sand and silicates | Identifying and mitigating the hidden risk in your supply chains

24th June 2025 supply chain

supply chain