Are you ready to shift from ESG to SDG?

You may have seen a recent article in The Economist describing the ESG movement as “Exaggerated, Superficial Guff… an unholy mess that needs to be ruthlessly streamlined”.

The limitation of the ESG concept is an issue that TDi Sustainability’s CEO, Assheton Stewart Carter, also raised during a recent talk to the faculty of Warwick Business School. Here Assheton puts in context what such a statement means for the industry, and why, in many ways it’s a sign of a sea change that’s already in motion. Read Assheton’s response to The Economist article below…

I agree with some of the problems with ESG raised by The Economist. ESG does have “a measurement problem”, and to suggest that the myriad topics summed up in this little acronym of “Environmental, Social and Governance” should be able to sit cosily under the same umbrella without conflict is naïve.

When sweeping statements of this nature arise, it is often an indication that we’re evolving as a culture and it’s time to reassess tools that may have grown outdated. To understand this fully we need to look a bit more closely at where the concept of ESG originated from.

When I was on the faculty at Warwick myself some 20 years ago, Corporate Social Responsibility – what we’re now calling ESG – was all about holding businesses accountable for managing their risk: responsible for obeying the law, and for understanding the risks they posed.

Dressed up as being “good” business, ESG was, in practice, more about protecting the organisation from risk, rather than protecting the world from harm.

Consequently, ESG-oriented compliance, reporting, and operation practices frameworks tend to be focused on the “issues” – on damage limitation – and on identifying risks. And of course, when you apply a risk lens, you only find… more risk.

Navigating the complex task of ranking and rating different comparable risks is one of the services we support our clients with at TDi Sustainability. So much so that we’ve created an industry-leading information platform in partnership with the Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI) – Material Insights – which can be used by companies to deepen their understanding of and mitigate against risks in supply chains, making it as easy as possible to access global networks of up-to-date information.

The expectation of most people who monitor corporate behaviour is to hold companies to account for managing risks. One methodological feature of such systems is “attribution” – in other words to ask to what extent a risk can be attributed to the actions or behaviour of a company, and where the boundaries of responsibility are to be drawn. The social contract between business and society is forever changing.

One of the main limitations of this ESG risk approach is that it tends to measure success through its “outputs”.

You need to show evidence of implementation of your management, which may be a policy document, training that has been completed, the presence of suitable equipment, that a documented system is in place with proof that people use it, and so on…

These types of results are then seen as proof of the system’s effectiveness. But, they don’t reveal whether the underlying problem that creates the risk to companies has been addressed.

Rather, they are content with a best-efforts mindset. After all, what can a single company possibly do when they are just a small part of a very large and complex economics system or extensive supply chain?

The problem with this approach is that it rewards the application of band aids, while ignoring the cause. In the medical field, preventative healthcare had its advent in the eighteenth century. CSR, in some form or another, has been around since the Quakers applied their principles to business, and it has been maturing as a discipline and business idea since then. ESG has, however, diverted that trajectory.

That is how ESG, or Corporate Social Responsibility, has evolved to date.

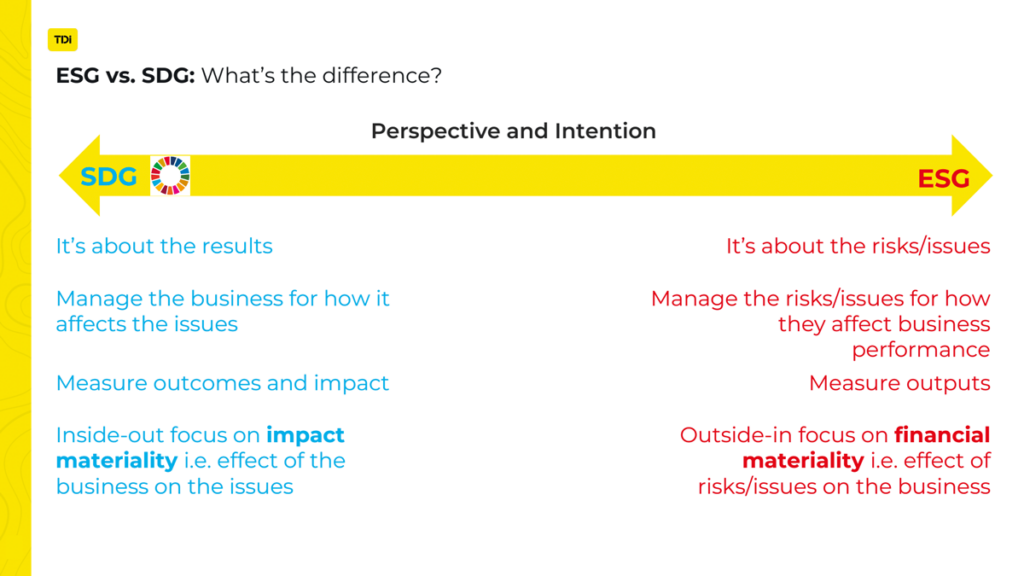

One of the biggest shifts we’re seeing now – both in how we advise our clients at TDi Sustainability, and in how new standards and global expectations are evolving – is a move away from ESG towards SDG (United Nations Sustainable Development Goals) – or Corporate Sustainability, which has a different perspective and intention.

Let me unpack what that means in practice.

SDG is based on the premise that a business should deliver goods and services which match the shifting social and economic conditions.

SDG asks companies to look more at how its business activities affect the world around it, rather than vice versa. The crucial difference is that SDG demands that we measure results, or “outcomes”.

Rather than weighing up whether a management system’s design meets international standards, such as ISO or OSHA for example – as we were doing with ESG – an SDG-focused management system asks, “What is the effect of this management system?” By this I mean, what geo-biophysical, social and political changes can be measured? For example, “Will it contribute to more or fewer trees?” Rather than, “Does it meet acceptable levels of deforestation?”

With SDG the attribution, the boundaries of who is responsible, are greyer. We’re no longer simply measuring against imposed standards, but upon localised effects relative to specific communities and landscapes.

The newly formed International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) and Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) climate reporting frameworks are now asking companies to report on “opportunities”; while the OECD talks of “leverage”.

What leverage does a company have to make positive changes?

Unlike ESG’s risk-lens, the focus has shifted now, so that it’s no longer just about managing negatives, but about identifying the positive opportunities available for companies to make a difference.

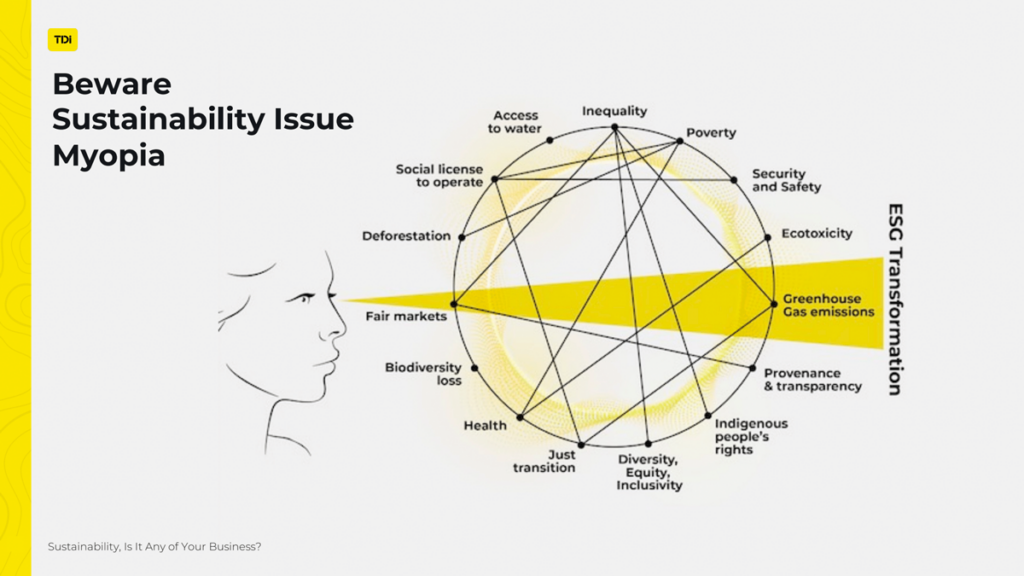

The question remains, what does this really mean for everyone pushing ESG-based agendas today? Should we ditch the “SG” and concentrate only on the “E” for Environment? Should we focus only on carbon, as The Economist article suggests?

On this point I couldn’t disagree more with their position. In fact, the trend towards carbon myopia poses a new level of risk to companies.

Over the past few years, we’ve seen another shift away from the core issues of environment, human rights, water, biodiversity and so on… to an era we’re in now where you can’t not talk about climate change.

If ESG regulations have been built around individual topics, then greenhouse gas emissions have become the number one measurement for all sustainability strategies.

But new regulations are reversing that trend to umbrella across a much bigger, more integrated picture. We’re moving from individuated ISO 14001 standards to comprehensive systems that do more, and cover all topics, incorporating carbon alongside water use, Indigenous Peoples’ Rights and everything beyond…

As of June 2022, France, Germany, Norway and Switzerland have all passed mandatory human rights and environmental due diligence legislation regulating business actors; while Austria, Belgium, Finland, the Netherlands, Spain and Sweden have signalled their intent to do the same.

Regionally, the European Commission released its Proposal for a Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence on February 23, 2022. The current trajectory of this “draft EU Directive” is pathbreaking, making access to the EU market for large regulated businesses contingent on the completion of due diligence that covers a wide swath of internationally recognized human rights and environmental challenges. Administrative penalties and civil remedies lie in wait for breaches of these obligations.

Globally, the third draft of the United Nations “Legally Binding Instrument to Regulate, in International Human Rights Law, the Activities of Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises” (the “draft UN Treaty”) is expected to make progress towards completion in 2022.

It’s clear that companies can no longer risk being too fixated on meeting individual standards, such as their greenhouse gas emissions alone.

Yes, we must continue identifying and measuring against risk and standards, because investors and rights groups want assurances that these are being measured and managed. But it’s also time for companies to move towards the SDG model, to show their contribution to society, because this is what both consumers and new standards are demanding.

The Economist article has shone a spotlight on evolutions that have long been brewing.

Where we stand, here in 2022, it’s clear that values have radically shifted. More than ever, the ability to be sustained as a business means meeting the culture and climate’s demand for sustainability by producing goods and services which create genuine and lasting value for people.

supply chain

supply chain

Re-defining legacy | Supporting companies and investors in achieving positive legacies in mining operations

3rd July 2025 supply chain

supply chain

Responsible sourcing of sand and silicates | Identifying and mitigating the hidden risk in your supply chains

24th June 2025 supply chain

supply chain